Mastering the Art of Casting: A Comprehensive Guide to Metal Forming Processes

Casting is a manufacturing process in which a liquid metal is poured into a mold cavity that matches the shape and size of the desired part. After cooling and solidification, the finished part or blank is obtained. This method is often referred to as liquid metal forming. Below is a detailed technical breakdown of modern casting technologies.

The Fundamental Process:

Liquid Metal → Mold Filling → Solidification & Shrinkage → Cast Part

Core Characteristics of Casting

Geometric Freedom: Capable of producing parts with any complex shape, particularly those with intricate internal cavities.

High Adaptability: Virtually no limits on alloy types or the physical size of the castings.

Resource Efficiency: Wide source of materials; scrap parts can be remelted, and equipment investment is relatively low.

Limitations: Higher scrap rates compared to some processes, lower surface quality in traditional methods, and demanding labor conditions.

Classification of Casting Processes

1. Sand Casting

Sand casting involves producing castings in a sand mold. This is the most common method for steel, iron, and most non-ferrous alloy castings.

Shutterstock

Technical Characteristics:

Suitable for complex shapes and intricate internal cavities.

Wide adaptability and low production costs.

For materials with poor plasticity (such as cast iron), it is often the only viable forming process.

Applications: Automotive engine blocks, cylinder heads, and crankshafts.

2. Investment Casting (Lost Wax Casting)

This process involves creating a pattern from a fusible material (like wax), coating it with layers of refractory material to form a shell, and then melting the pattern out to leave a seamless mold.

Pros & Cons:

Advantages: High dimensional and geometric accuracy; excellent surface finish; capable of casting complex shapes in almost any alloy.

Disadvantages: Complex procedures and higher costs.

Applications: Small parts requiring high precision, such as turbine blades for jet engines.

3. Die Casting

Die casting uses high pressure to force molten metal at high speeds into a precision metal mold cavity (die). The metal solidifies under pressure.

Pros & Cons:

Advantages: High pressure and flow velocity result in excellent product quality, stable dimensions, and high interchangeability. High production efficiency and mold durability.

Disadvantages: Parts may develop tiny pores or shrinkage porosity; lower plasticity makes it unsuitable for high-impact or vibrating loads.

Applications: Automotive components, instrumentation, electronics, and medical devices.

4. Low-Pressure Casting

This method involves filling the mold with liquid metal under low pressure (0.02–0.06 MPa) and allowing it to crystallize under that pressure.

Technical Characteristics:

Adjustable pressure and velocity, making it suitable for various molds (metal or sand) and casting sizes.

Bottom-filling ensures smooth flow, preventing gas entrapment and mold wall erosion.

Dense crystalline structure and high mechanical properties.

High metal utilization (90–98%) due to the lack of traditional risers.

Applications: Traditional automotive parts like cylinder heads and wheel hubs.

5. Centrifugal Casting

Molten metal is poured into a rotating mold, where centrifugal force distributes the liquid against the mold walls to solidify.

Pros & Cons:

Advantages: Minimal metal consumption in gating/riser systems; hollow parts can be made without cores; high density with fewer gas pores or slag inclusions.

Disadvantages: Limited to specific geometries; internal diameter accuracy is low and surface quality of the inner bore is rough.

Applications: Cast iron pipes, internal combustion engine cylinder liners, and bushings.

6. Gravity Die Casting (Permanent Mold Casting)

Liquid metal fills a metal mold under the force of gravity and solidifies within it.

Pros & Cons:

Advantages: High thermal conductivity of the mold leads to faster cooling and denser structures (15% higher mechanical properties than sand casting). Higher dimensional accuracy.

Disadvantages: Molds lack permeability, requiring venting measures; lack of mold “give” (collapsibility) can lead to cracks during solidification. High mold manufacturing costs.

Applications: Large-scale production of non-ferrous alloys (aluminum, magnesium) and iron castings.

7. Vacuum Die Casting

An advanced die-casting process that eliminates or significantly reduces gas pores by evacuating the air from the mold cavity before injection.

Pros & Cons:

Advantages: Improved mechanical properties and surface quality; allows for thinner-walled castings; reduces back-pressure in the cavity.

Disadvantages: Complex mold sealing structures and higher costs.

8. Squeeze Casting

Squeeze casting solidifies liquid or semi-solid metal under high pressure to directly obtain parts or blanks.

Technical Characteristics:

Direct Squeeze: Spraying lubricant → Pouring alloy → Closing mold → Pressurizing → Holding→ Releasing → Ejection.

Indirect Squeeze: Includes an injection/filling stage similar to die casting before the high-pressure solidification.

Benefits: Eliminates internal pores/shrinkage; high dimensional accuracy; prevents casting cracks.

Applications: Various alloys including aluminum, zinc, copper, and ductile iron.

9. Lost Foam Casting

A type of evaporative-pattern casting. A foam pattern (matching the part size) is coated with refractory paint, buried in dry sand, and vibrated. During pouring, the metal vaporizes the foam and occupies its space.

Technical Characteristics:

High precision and no need for sand cores, reducing machining time.

No parting line, allowing for high design flexibility.

Clean production with reduced environmental impact.

Applications: Complex precision castings like engine blocks and high-manganese steel pipes.

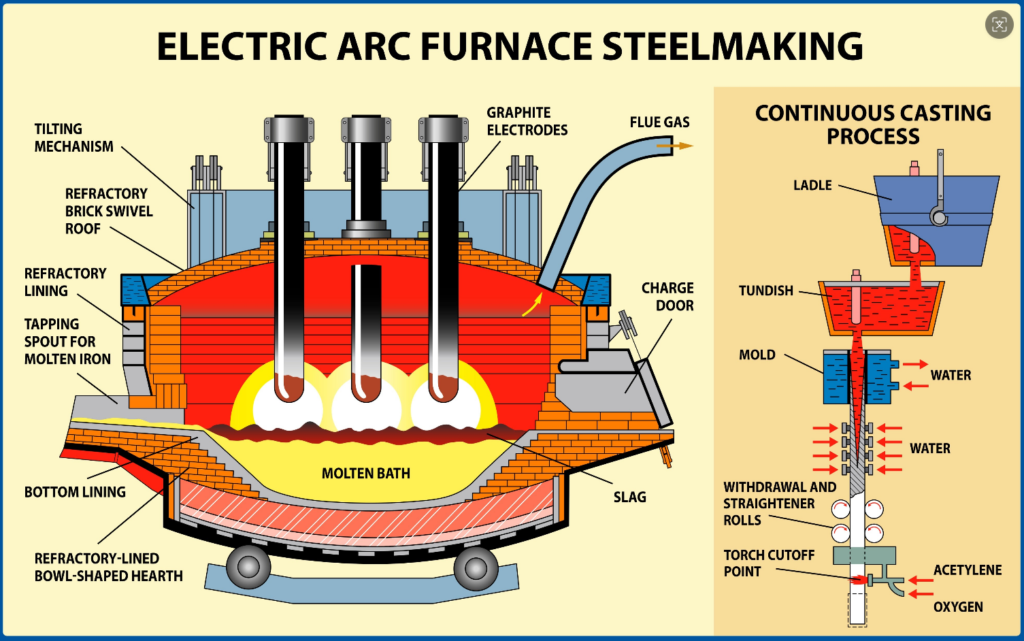

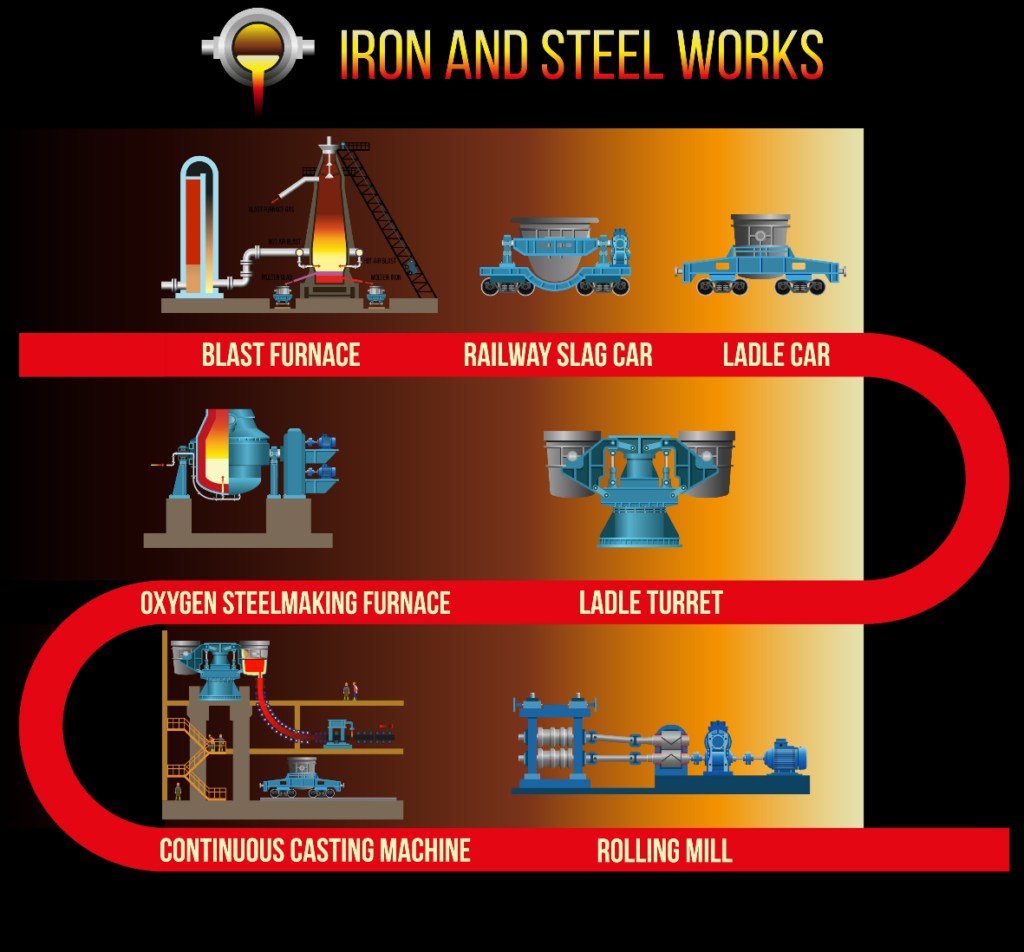

10. Continuous Casting

Molten metal is continuously poured into a specialized metal mold called a crystallizer. The solidified shell is continuously pulled out from the other end, allowing for specific or arbitrary lengths.

Shutterstock

Technical Characteristics:

Dense crystallization and uniform structure due to rapid cooling.

Saves metal and increases yield.

Simplifies the process by eliminating traditional molding steps; easy to automate.

Applications: Long castings with constant cross-sections, such as steel billets, slabs, rods, and pipes.